交感神经系统与副交感神经系统

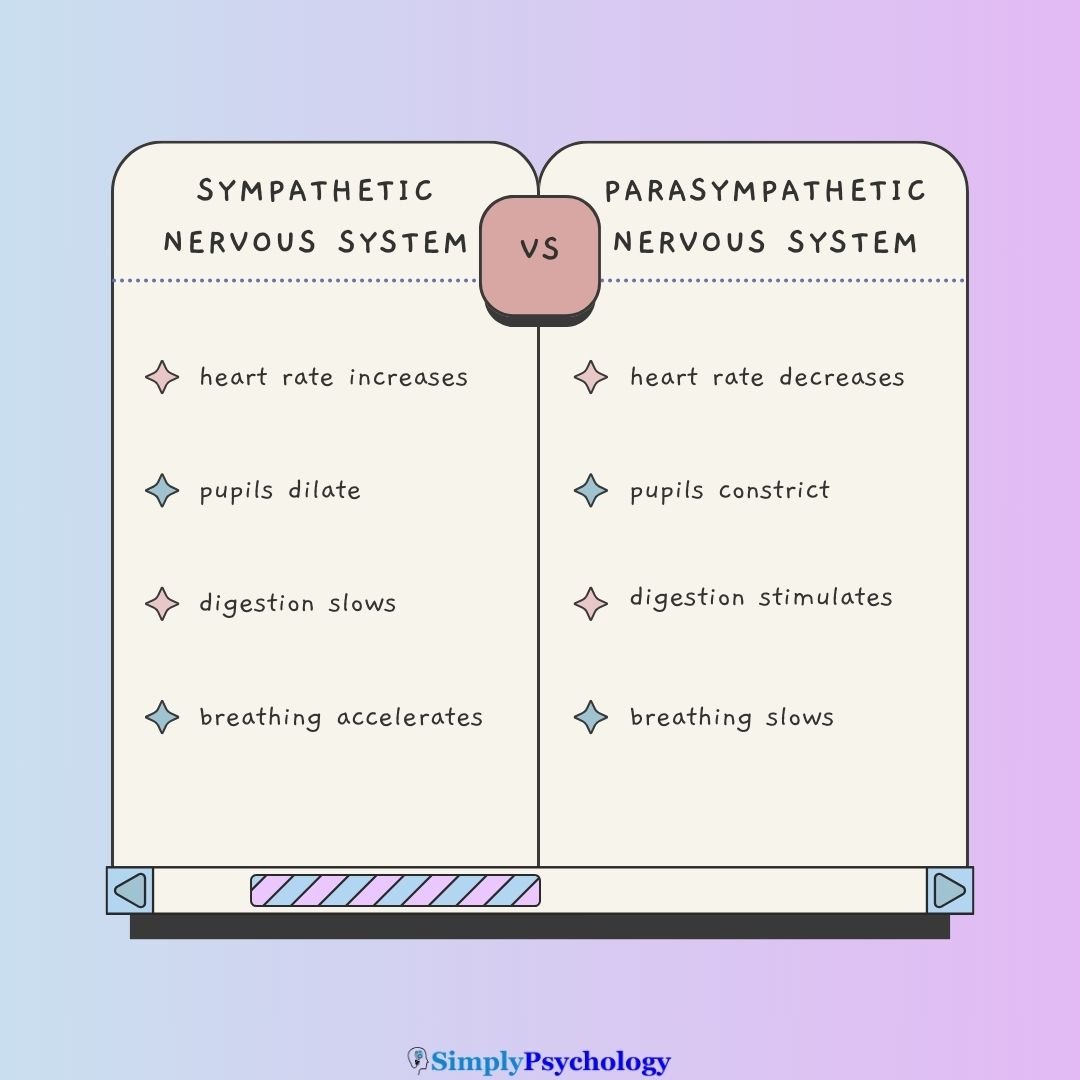

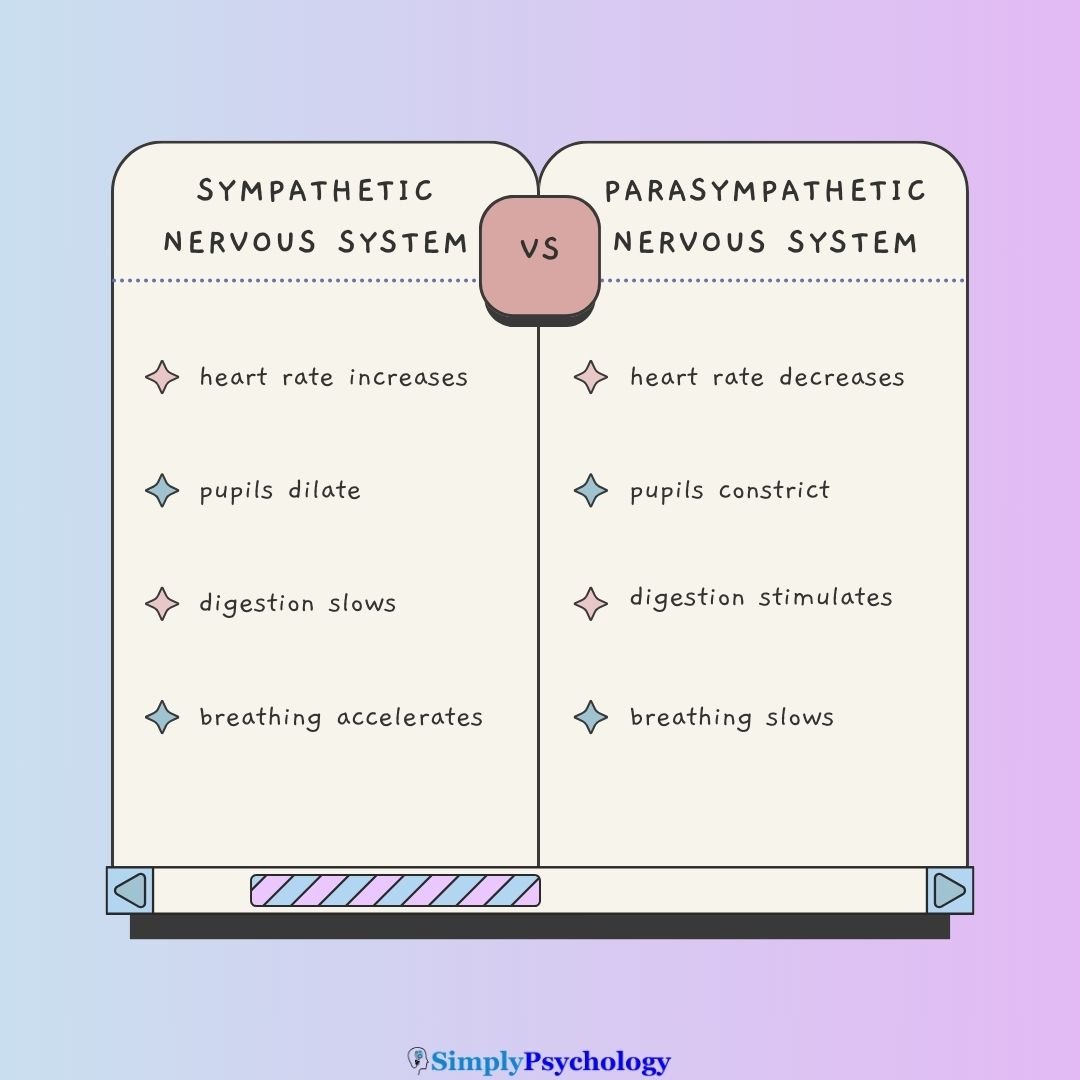

The sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are the two main branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which controls involuntary functions like heart rate, breathing, and digestion.

The sympathetic system acts like a gas pedal, activating the fight-or-flight response in stressful situations, while the parasympathetic system acts like the brakes, promoting rest and recovery after stress.

Key Takeaways

- The sympathetic system triggers the fight-or-flight response, increasing heart rate and alertness.

- The parasympathetic system activates rest-and-digest functions, promoting relaxation and recovery.

- Both are part of the autonomic nervous system and help maintain internal balance (homeostasis).

- The vagus nerve is key to parasympathetic calming effects on the heart, lungs, and digestion.

- Stress management techniques like breathing and mindfulness support nervous system balance.

Autonomic Nervous System Overview

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is part of the peripheral nervous system and controls automatic functions like heart rate, pupil size, and gland activity.

It has two main branches—sympathetic and parasympathetic—which often have opposite effects on the same organs.

Together, they maintain homeostasis, keeping the body balanced. For instance, if the sympathetic system raises your heart rate during stress, the parasympathetic system brings it back down afterward.

Key Differences Between Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Systems

| Aspect | Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) “Fight-or-Flight” | Parasympathetic Nervous System (PSNS) “Rest-and-Digest” |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Function | Prepares body for rapid action in emergencies or stress (energy mobilization). | Calms the body and conserves energy, promoting relaxation and routine maintenance. |

| Origin (Spinal Regions) | Thoracic & lumbar spinal cord (middle of spinal cord). Preganglionic fibers are short, synapsing in ganglia near the spine. | Brainstem (cranial nerves III, VII, IX, X) and sacral spinal cord. Preganglionic fibers are long, synapsing in ganglia near target organs. |

| Neuron Pathways | Short, fast pathways – enables a quick, widespread response (signals travel quickly to multiple organs). | Longer pathways – slower, more targeted response (signals are more localized and slower to activate). |

| Heart (Cardiovascular) | Increases heart rate and force of contraction (pumps more blood to muscles). Blood pressure rises. | Decreases heart rate and contraction force (resting heartbeat). Blood pressure lowers toward normal. |

| Lungs (Respiratory) | Dilates bronchial tubes in lungs for easier airflow (breathing rate increases). | Constricts bronchial tubes (reduces airflow to resting needs). Breathing rate decreases. |

| Eyes (Pupils) | Dilates pupils (more light in for improved far vision). | Constricts pupils (protects retina; normal vision focus). |

| Muscles (Skeletal) | Tenses muscles and increases blood flow to skeletal muscles (priming body for movement). | Relaxes muscles and directs blood flow back to internal organs (restful state). |

| Digestive System | Inhibits digestion: decreases stomach movement and secretions; liver releases glucose for energy instead of digesting food. Saliva production decreases (dry mouth). | Stimulates digestion: increases stomach activity and secretions; liver stores energy (glycogen). Saliva production increases (helps digestion). |

| Urinary/Bladder | Reduces urinary output: bladder wall relaxes and sphincter contracts (you hold urine during stress). | Increases urinary output: bladder contracts and sphincter relaxes (normal urination resumes). |

| Adrenal Glands | Stimulates adrenal glands to release adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline, boosting alertness and energy. | No direct effect on adrenal medulla (no surge of adrenaline in calm states). |

| Primary Neurotransmitters | Uses adrenergic neurons (releasing norepinephrine/epinephrine). Preganglionic fibers release acetylcholine, but most postganglionic fibers release norepinephrine. | Uses cholinergic neurons (releasing acetylcholine at both pre- and postganglionic fibers). Acetylcholine promotes calming effects on organs. |

Note: Both systems are constantly active to some degree and balance each other. The sympathetic division turns up certain functions while the parasympathetic turns them down, and vice versa, depending on what the body needs at any moment.

Sympathetic Nervous System in Detail (Fight-or-Flight)

In threatening or high-pressure situations, the SNS rapidly prepares the body to face danger or flee from it.

This response evolved as a survival mechanism – it provides a burst of energy and alertness to handle emergencies.

When the sympathetic system fires, stress hormones like adrenaline (epinephrine) are released into the bloodstream, causing immediate physiological changes:

- Heart beats faster and stronger: The heart rate spikes and the heart contracts more forcefully, pushing blood to muscles and vital organs. This ensures your muscles have plenty of oxygen and nutrients to respond to the threat.

- Breathing accelerates: The bronchi in the lungs widen, allowing more air in. You start breathing quicker and deeper to increase oxygen intake. More oxygen is available for the brain and muscles, sharpening your alertness.

- Pupils dilate: Your eyes widen (pupils enlarge) to take in more light and improve vision, especially distance vision, which can help identify threats.

- Muscles tense up: Blood flow is diverted toward skeletal muscles, priming them for quick action. You might feel your muscles tighten, ready to spring into movement if needed.

- Digestion slows or pauses: Digestive processes are put on hold. Saliva production decreases (hence a dry mouth when anxious), and the stomach’s activity slows down. The body conserves energy by not digesting food during an emergency, since digestion isn’t critical for immediate survival.

- Pain perception may decrease: In the heat of the moment, the fight-or-flight response can dull pain (an adaptive benefit so that pain doesn’t debilitate you until you reach safety). This is why injuries might not be felt until after a stressful event is over (though this involves complex hormone effects beyond just the SNS).

- Energy release increases: The liver converts glycogen to glucose, raising blood sugar levels to provide quick energy fuel for muscles. At the same time, the adrenal glands dump adrenaline into your system, heightening your overall alertness and strength.

These changes happen within seconds because the sympathetic nervous system is built for speed.

Its short preganglionic neurons connect to a chain of ganglia near the spine, allowing signals to spread quickly to multiple organs.

This fast setup means you might react—heart racing—before you’re even fully aware of the threat. The SNS rapidly mobilizes the body to survive or escape danger.

Parasympathetic Nervous System in Detail (Rest-and-Digest)

The parasympathetic nervous system has the opposite role of the sympathetic system: it calms the body and supports restoration and energy conservation after stress.

Its signals come from the brainstem (via cranial nerves, especially the vagus nerve) and the sacral spinal cord, which is why it’s sometimes called the craniosacral division of the autonomic nervous system.

When active, the parasympathetic system essentially reverses the effects of the sympathetic response, guiding the body back to a balanced, restful state.

- Heart rate slows: Your heart rate decreases back toward a normal, resting rate. The force of each heartbeat also diminishes. This conserves energy and prevents wear on the heart after the stress has passed.

- Breathing becomes slower and shallow: The bronchi in the lungs constrict again, since high volumes of air are no longer needed. You begin breathing more slowly. Often, exhaling might lengthen as you relax (sometimes why taking slow deep breaths can engage the parasympathetic response).

- Pupils constrict: Your pupils shrink back to a normal size. This helps normalize vision and protect the retina now that you’re in a calmer, well-lit environment (dilated pupils let in more light than needed when safe).

- Muscles relax: Blood is redirected from the muscles to internal organs. The tension in skeletal muscles eases off, and you might feel your body unclench or even experience a sense of lightness as the adrenaline wears off.

- Digestion resumes: Saliva production increases again (mouth moistens) and digestive enzymes and stomach activity pick up to process food. You may even feel hunger or thirst once you relax, since the body is attending to digestion and hydration signals. The parasympathetic system stimulates intestinal motility and secretion, helping your body digest and absorb nutrients.

- Urination and defecation normalize: The bladder and bowel walls constrict while the sphincter muscles relax, allowing normal elimination to occur. This is why after a stressful scare, you might suddenly feel the need to use the bathroom once you’re safe – the parasympathetic system is back in charge of those functions.

- “Feed and breed” functions: In restful states, not only is digestion (feeding) promoted, but reproductive organs receive more blood flow as well, supporting sexual arousal and other reproductive processes.

While the sympathetic nervous system activates the body quickly and broadly, the parasympathetic response is slower and more targeted.

Much of this calming effect is carried out by the vagus nerve, which sends signals from the brain to organs like the heart, lungs, and digestive system to help restore balance.

How do the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems work together?

The sympathetic and parasympathetic systems work like a finely tuned see-saw, constantly adjusting to keep the body in homeostasis—a stable internal balance. They rarely operate in isolation.

Instead, they function in opposition but also in coordination, with one system dialing up activity while the other dials it down depending on the situation.

For example, during a stressful event—like narrowly avoiding a car accident—the sympathetic nervous system takes over.

Your heart races, muscles tense, and breathing quickens as your body prepares for action. This is the classic fight-or-flight response, driven by adrenaline and norepinephrine.

Once the threat passes, the parasympathetic nervous system steps in to calm things down. It slows your heart rate, relaxes your muscles, and restarts digestion.

You may feel shaky or exhausted—signs your body is transitioning back to its resting state.

In a healthy body, both systems are active to some degree. The sympathetic system maintains readiness, while the parasympathetic system supports recovery.

This balance is essential.

Chronic overactivation of the sympathetic system can lead to high blood pressure, anxiety, and sleep problems.

Meanwhile, excessive parasympathetic influence can cause symptoms like dizziness or fainting in rare cases.

Together, these two systems help the body respond to challenges and recover afterward, maintaining the stability needed for everyday function.ReviewerAuthor

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

交感神经系统与副交感神经系统

交感神经系统就像油门踏板,在压力情况下激活战斗或逃跑反应,而副交感系统就像刹车,促进压力后的休息和恢复。

要点

- 交感神经系统触发战斗或逃跑反应,增加心率和警觉性。

- 副交感系统激活休息和消化功能,促进放松和恢复。

- 两者都是自主神经系统的一部分,有助于维持内部平衡(体内平衡)。

- 迷走神经是副交感神经对心脏、肺和消化的镇静作用的关键。

- 呼吸和正念等压力管理技巧可以支持神经系统的平衡。

自主神经系统概述

自主神经系统 ( ANS )是周围神经系统的一部分,控制心率、瞳孔大小和腺体活动等自动功能。

它有两个主要分支——交感神经和副交感神经——它们通常对同一器官产生相反的作用。

它们共同维持体内平衡,保持身体平衡。例如,如果交感系统在压力下提高你的心率,副交感系统会在之后降低心率。

交感神经系统和副交感神经系统之间的主要区别

| 方面 | 交感神经系统(SNS) “战斗或逃跑” | 副交感神经系统(PSNS) “休息和消化” |

|---|---|---|

| 整体功能 | 使身体做好准备,以便在紧急情况或压力下迅速采取行动(能量动员)。 | 镇静身体并保存能量,促进放松和日常维护。 |

| 起源(脊柱区域) | 胸椎和腰椎脊髓(脊髓中部)。节前纤维很短,在脊柱附近的神经节中形成突触。 | 脑干(脑神经 III、VII、IX、X)和骶脊髓。节前纤维很长,在靶器官附近的神经节中形成突触。 |

| 神经元通路 | 短而快的通路——能够实现快速、广泛的反应(信号快速传播到多个器官)。 | 更长的通路——更慢、更有针对性的反应(信号更加局部化并且激活更慢)。 |

| 心脏(心血管) | 增加心率和收缩力(将更多血液泵入肌肉)。血压升高。 | 降低心率和收缩力(静息心跳)。血压降至正常水平。 |

| 肺(呼吸系统) | 扩张肺部支气管以促进气流(呼吸频率增加)。 | 收缩支气管(减少气流以满足休息需要)。呼吸频率降低。 |

| 眼睛(学生) | 扩张瞳孔(更多光线进入以改善远视力)。 | 收缩瞳孔(保护视网膜;正常视力焦点)。 |

| 肌肉(骨骼) | 紧张肌肉并增加骨骼肌的血流量(为身体运动做好准备)。 | 放松肌肉并引导血液流回内脏(安静状态)。 |

| 消化系统 | 抑制消化:减少胃运动和分泌;肝脏释放葡萄糖作为能量,而不是消化食物。唾液分泌减少(口干)。 | 刺激消化:增加胃活动和分泌;肝脏储存能量(糖原)。唾液分泌增加(帮助消化)。 |

| 泌尿/膀胱 | 减少尿量:膀胱壁松弛,括约肌收缩(在压力下你会憋尿)。 | 增加尿量:膀胱收缩,括约肌放松(恢复正常排尿)。 |

| 肾上腺 | 刺激肾上腺释放肾上腺素和去甲肾上腺素,提高警觉性和精力。 | 对肾上腺髓质没有直接影响(平静状态下肾上腺素不会激增)。 |

| 主要神经递质 | 使用肾上腺素能神经元(释放去甲肾上腺素/肾上腺素)。节前纤维释放乙酰胆碱,但大多数节后纤维释放去甲肾上腺素。 | 使用胆碱能神经元(在节前和节后纤维释放乙酰胆碱)。乙酰胆碱促进器官的镇静作用。 |

注意:两个系统在某种程度上都持续活跃并相互平衡。交感神经激活某些功能,而副交感神经则关闭某些功能,反之亦然,具体取决于身体随时的需要。

交感神经系统详细信息(战斗或逃跑)

在受到威胁或高压的情况下,SNS 会迅速让身体做好面对危险或逃离危险的准备。

这种反应演变为一种生存机制——它提供了处理紧急情况的能量爆发和警觉性。

当交感神经系统兴奋时,肾上腺素等应激激素会释放到血液中,立即引起生理变化:

- 心跳更快更强:心率加快,心脏收缩更有力,将血液推向肌肉和重要器官。这可以确保您的肌肉有充足的氧气和营养来应对威胁。

- 呼吸加速:肺部的支气管变宽,允许更多空气进入。您开始呼吸得更快更深,以增加氧气摄入量。更多的氧气可供大脑和肌肉使用,从而提高您的警觉性。

- 瞳孔放大:您的眼睛睁大(瞳孔放大)以吸收更多光线并改善视力,尤其是远视力,这可以帮助识别威胁。

- 肌肉紧张:血液流向骨骼肌,为它们快速行动做好准备。您可能会感觉肌肉收紧,准备好在需要时开始运动。

- 消化减慢或暂停:消化过程被搁置。唾液分泌减少(因此焦虑时口干),胃的活动减慢。身体在紧急情况下通过不消化食物来保存能量,因为消化对于立即生存并不重要。

- 疼痛感知可能会减少:在最激烈的时刻,“战斗或逃跑”反应可以减轻疼痛(一种适应性益处,这样疼痛就不会令您虚弱,直到您到达安全地带)。这就是为什么直到压力事件结束后才可能感觉到受伤(尽管这涉及复杂的激素影响,而不仅仅是 SNS)。

- 能量释放增加:肝脏将糖原转化为葡萄糖,提高血糖水平,为肌肉提供快速的能量燃料。与此同时,肾上腺将肾上腺素释放到您的系统中,提高您的整体警觉性和力量。

这些变化会在几秒钟内发生,因为交感神经系统是为速度而生的。

它的短节前神经元连接到脊柱附近的一系列神经节,使信号能够快速传播到多个器官。

这种快速的设置意味着您可能会在完全意识到威胁之前就做出反应——心跳加速。 SNS迅速调动身体以求生存或逃离危险。

副交感神经系统详细信息(休息和消化)

副交感神经系统具有与交感系统相反的作用:它使身体平静并支持压力后的恢复和能量保存。

它的信号来自脑干(通过颅神经,特别是迷走神经)和骶脊髓,这就是为什么它有时被称为自主神经系统的颅骶部分。

当副交感神经系统活跃时,它本质上会逆转交感神经反应的影响,引导身体回到平衡、宁静的状态。

- 心率减慢:您的心率下降回到正常的静息心率。每次心跳的力量也会减弱。这样可以节省能量并防止压力过后心脏磨损。

- 呼吸变得更慢、更浅:肺部的支气管再次收缩,因为不再需要大量的空气。你的呼吸开始变慢。通常,当您放松时,呼气可能会延长(有时缓慢深呼吸会引起副交感神经反应)。

- 瞳孔收缩:您的瞳孔缩小到正常大小。这有助于使视力正常并保护视网膜,因为您处于一个更平静、光线充足的环境中(散瞳的瞳孔会进入比安全时需要的更多的光线)。

- 肌肉放松:血液从肌肉重新引导到内脏。骨骼肌的紧张感减轻,您可能会感觉身体松弛,甚至随着肾上腺素的消退而体验到一种轻松感。

- 消化恢复:唾液分泌再次增加(口腔湿润),消化酶和胃活动恢复以处理食物。一旦放松,您甚至可能会感到饥饿或口渴,因为身体正在处理消化和补水信号。副交感系统刺激肠道蠕动和分泌,帮助您的身体消化和吸收营养。

- 排尿和排便正常化:膀胱和肠壁收缩,而括约肌放松,从而可以正常排泄。这就是为什么在一次紧张的惊吓之后,一旦安全了,您可能会突然觉得需要上厕所——副交感神经系统又重新负责这些功能。

- “喂养和繁殖”功能:在安静的状态下,不仅促进消化(喂养),而且生殖器官也会获得更多的血流,支持性唤起和其他生殖过程。

交感神经系统快速而广泛地激活身体,而副交感神经系统的反应则较慢且更有针对性。

这种镇静作用大部分是由迷走神经实现的,迷走神经将信号从大脑发送到心脏、肺和消化系统等器官,以帮助恢复平衡。

交感神经系统和副交感神经系统如何协同工作?

交感神经和副交感神经系统就像一个微调的跷跷板,不断调整以保持身体处于稳态——稳定的内部平衡。他们很少单独行动。

相反,它们既相互对立,又相互协调,一个系统加大活动力度,而另一个系统则根据情况减弱活动。

例如,在发生压力事件时(比如险些发生车祸),交感神经系统 就会发挥作用。

当您的身体准备采取行动时,您的心跳加速、肌肉紧张、呼吸加快。这是典型的战斗或逃跑反应,由肾上腺素和去甲肾上腺素驱动。

一旦威胁过去,副交感神经系统就会介入,让事情平静下来。它会减慢你的心率,放松你的肌肉,并重新开始消化。

您可能会感到颤抖或疲惫——这表明您的身体正在恢复休息状态。

在健康的身体中,这两个系统都在某种程度上活跃。交感神经系统保持准备状态,而副交感神经系统支持恢复。

这种平衡至关重要。

交感系统慢性过度激活会导致高血压、焦虑和睡眠问题。

同时,在极少数情况下,过度的副交感神经影响会导致头晕或昏厥等症状。

这两个系统共同帮助身体应对挑战并随后恢复,保持日常功能所需的稳定性。

审稿人作者

曼彻斯特大学心理学学士(荣誉)、研究硕士、博士

《简单心理学》主编